« Tout Positif » ?

L’expression « éducation tout positif » ou « éducation 100% positif » s’est largement imposée dans le monde canin. Elle est souvent présentée comme moderne, scientifique et respectueuse du chien. Pourtant, derrière cette formule séduisante se cachent trois confusions majeures : une erreur sémantique, une compréhension approximative du fonctionnement du cerveau, et une lecture incomplète du langage canin. L’objectif ici n’est pas d’opposer des camps, mais de clarifier des concepts qui, mal compris, peuvent nuire autant au chien qu’à l’humain.

1. Une erreur sémantique : bienveillance n’est pas « ajout »

Il est essentiel de le dire clairement : la bienveillance doit guider toute personne qui éduque un chien. Sur ce point, il n’y a aucun désaccord. Là où la confusion apparaît, c’est lorsque la bienveillance est assimilée au seul « positif », entendu comme l’ajout systématique de récompenses.

En sciences du comportement, les mots positif And négatif n’ont aucune valeur morale. Ils décrivent uniquement un mécanisme : l’ajout ou le retrait d’un stimulus.

- Renforcement positif : on ajoute quelque chose pour augmenter un comportement

- Renforcement négatif : on retire quelque chose pour augmenter un comportement.

- Punition positive : on ajoute quelque chose pour diminuer un comportement.

- Punition négative : on retire quelque chose pour diminuer un comportement.

Voir aussi cet article pour plus de détails Éduquer son berger allemand

Assimiler positif à bien And négatif à mal est une erreur de langage qui entraîne une erreur de raisonnement. La bienveillance relève de l’intention et de la qualité de la relation, pas du type d’outil utilisé.

Un parallèle simple permet de le comprendre : un enfant à qui l’on cède tout, sans jamais poser de limite claire, n’est généralement ni plus apaisé ni plus heureux. Il devient souvent dépendant, frustré au moindre refus, et démuni face à la réalité. L’absence de cadre n’est pas une preuve d’amour ; c’est souvent une difficulté à assumer le rôle éducatif.

Chez le chien, le mécanisme est comparable : la bienveillance ne consiste pas à tout autoriser, mais à accompagner l’apprentissage avec cohérence et lisibilité.

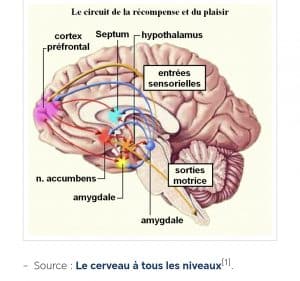

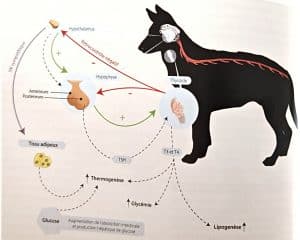

2. Une compréhension incomplète du fonctionnement du cerveau

Le cerveau du chien (comme celui de l’humain) apprend par association, anticipation et régulation émotionnelle. Il ne fonctionne pas uniquement sur la recherche de récompense.

Réduire l’apprentissage à la seule activation du circuit dopaminergique (friandises, jouets, excitation) pose plusieurs problèmes :

- la dopamine motive l’action, mais ne structure pas à elle seule le comportement ;

- un chien peut être très motivé… et très instable ;

- l’absence de cadre clair augmente l’incertitude, donc le stress.

Le cerveau a besoin de prévisibilité. Cela passe par des règles cohérentes, des limites compréhensibles et des conséquences lisibles. Or, une éducation exclusivement axée sur la récompense immédiate néglige souvent cette dimension structurante.

– Source « Psychiatrie vétérinaire du chien » editions Noledge

Apprendre, ce n’est pas seulement rechercher le plaisir : c’est aussi intégrer ce qui est attendu, ce qui ne l’est pas, et pourquoi.

3. Un manque de compréhension du langage canin et social

Le chien communique principalement par :

- la posture,

- la gestuelle,

- les micro-signaux,

- la distance et le mouvement.

Son langage est largement régulateur et inhibiteur. Dans les interactions canines et inter-espèces naturelles, l’apprentissage passe très peu par la récompense et beaucoup, voire même essentiellement par l’ajustement social.

Les travaux décrits notamment dans Psychiatrie vétérinaire du chien (Masson, Bleuer, Muller, Pageat) rappellent le rôle fondamental de la mère et des congénères dans l’acquisition des auto-contrôles. Le chiot apprend à se comporter correctement à travers :

- le refus de contact physique,

- l’interruption du jeu,

- les grognements,

- et, si nécessaire, des morsures inhibées allant jusqu’au gémissement du chiot.

Ces réponses ne sont ni violentes ni pathologiques : elles sont structurantes et surtout elles sont le langage canin, que l’on le veuille ou non. Elles permettent au chiot d’intégrer les limites, de calibrer son comportement et de développer une véritable régulation émotionnelle.

Les vétérinaires cités ci-dessus mettent en avant que la privation de ces contacts, d’apparence rustres pour ne pas dire brutaux, augmente la probabilité que le chiot développe des troubles du comportement !

En cherchant à éliminer toute forme de frustration, d’opposition ou de contrainte, on s’éloigne du fonctionnement réel du chien et de son système d’apprentissage social. Une limite claire, exprimée de manière calme et proportionnée, est perçue comme une information, pas comme une agression.

Un cadre lisible est souvent plus rassurant qu’une succession de récompenses distribuées sans lecture fine du comportement.

4. Le risque du dogmatisme et la perte d’outils utiles

Le problème majeur n’est pas l’usage du renforcement positif, mais le fait de se priver volontairement d’autres leviers par principe idéologique.

Un exemple simple, universel et non violent illustre parfaitement le renforcement négatif : le bip sonore de la ceinture de sécurité. Le son cesse lorsque la ceinture est attachée. Ce mécanisme sauve des vies, ne provoque ni douleur ni traumatisme, et n’est contesté par personne (sauf sur le moment quand on met sa ceinture en pestant 😅).

En éducation canine, refuser par dogme tout outil relevant du retrait, de la contrainte même physique ou de la désapprobation prive le chien d’informations pourtant naturelles pour lui.

Sur le terrain, cette approche montre ses limites notamment avec :

- des chiens traumatisés,

- des chiens à très forts caractères,

- des lignées sélectionnées pour l’initiative et la résistance,

- ou des chiens déjà installés dans des comportements problématiques.

Dans ces situations, comprendre et savoir utiliser l’ensemble des stratégies disponibles est indispensable pour éviter l’impasse éducative. L’objectif n’est jamais de contraindre pour contraindre, mais de trouver le juste équilibre entre motivation, cadre et sécurité.

L’éducation canine gagne à être pragmatique plutôt que dogmatique, et adaptée à l’individu plutôt qu’à une idéologie.

Conclusion : sortir du slogan, revenir au vivant

L’éducation canine n’est ni une affaire de morale, ni une recette universelle. C’est une rencontre entre deux systèmes nerveux différents.

Sortir du « tout positif », ce n’est pas revenir à la brutalité. C’est accepter que :

- le chien a besoin de plaisir et de structure,

- la bienveillance n’exclut pas la clarté,

- comprendre un chien implique de parler sa langue, pas seulement de projeter la nôtre.

En éducation comme ailleurs, les slogans rassurent. La compréhension, elle, demande un peu plus d’effort… mais elle respecte davantage le vivant.